A Royal Injustice?

The year is 1840, the date 10 June, a warm and dry Wednesday evening, just the weather for a pleasant drive to take in the early summer air. So it seemed to the young Queen Victoria and her new husband, Prince Albert.

They had been married only four months to the day, but these evening drives had already become something of a habit for them. Londoners had begun to wait in anticipation for their open carriage to swing out of the gates of Buckingham Palace and turn left up Constitution Hill towards the parks. Not all in the crowds, though, were well-wishers. For that evening a young bartender lodging in West Street, Lambeth, had brought with him two loaded pistols to kill Victoria, her husband, or both. His name was Edward Oxford, and this was the first of numerous assassination attempts on the Queen during her long reign.

Oxford would be declared insane at his trial and was detained at first in Bethlem Hospital and then Broadmoor, was eventually declared sane and emigrated to Australia under the name of John Freeman.

All this is well known and the details are readily available in the blogosphere. But what isn't so well known, indeed remained unknown until recently pieced together, is another story of incarceration directly connected to that June evening in 1840.

Edward Oxford's first shot had been heard by many in the waiting crowd, and the would-be assassin was spotted by a young man and a boy jogging to keep pace with the royal carriage. Joshua Reeve Lowe sprinted across Constitution Hill and reached Oxford just as he fired the second pistol. Lowe and his schoolboy nephew were the first to lay hands on Oxford and seize his guns. Joshua Reeve Lowe would be the lead prosecution witness at Oxford's Bow Street arraignment and then at the Old Bailey trial. Lowe's name and occupation - he was a spectacle-maker and optician in Copthall Court, near the Bank of England - were front-page news on every breakfast table in the nation. Lowe's 'fifteen minutes of fame' would have life-changing consequences that proved a disaster for him.

Lowe's sudden celebrity, acknowledged by the highest in the land - his business was patronised briefly by Prince Albert and by the Queen Mother - led him to take a momentous decision. He would tear himself from his City roots - he was born and bred there - and set up business in the heart of the West End. He advertised his new venture at 34 St James's Street in the summer of 1841 as 'Joshua Reeve Lowe, Optician, by Special Appointment to HRH Prince Albert, and under the immediate patronage of the Queen Dowager and HRH the Duchess of Kent.' But the 'immediate patronage' proved worthless. The rich and noble customers he sought stayed away, his valuable stock remained unsold, his debts within weeks totalled nearly £4000 (some half a million at today's prices), and to salvage something from the wreck he moved his business to Hatfield Street, off the Waterloo Road. There he was arrested by a creditor who refused to wait any longer for his money, and on 13 December he was brought into custody in the Marshalsea Prison, off Borough High Street, Southwark. Unable to settle with his creditors he remained a prisoner until January 1843. He made clear to the Insolvent Debtors' Court that he felt sadly let down: 'He expected, he said, to be made a Court tradesman, as in the case of the person who saved the life of George the Third from the hand of an assassin; but his expectations were not realised.' In fact, the only help he had received was from Prince Albert, who bought a telescope from him for £70.

Joshua Reeve Lowe never recovered from the crash, or his imprisonment. He died at his home at 15 Broadway, Southwark, on 25 January 1848. The cause of death was given as 'Phthisis', probably chronic pulmonary tuberculosis; if so, it can't have been helped by so many months in Southwark's prisons. He was just 37.

Just a few years earlier he had been the hero of the hour, a celebrity who believed his actions - and the royal gratitude that would surely follow - would change his life forever. It did change, but not in the way he had hoped. Was he a victim of royal ingratitude? Or was he an innocent abroad whose expectations could never have been realised? Either way, Joshua Reeve Lowe's rise and fall can serve as a Victorian morality tale of London, 1840.

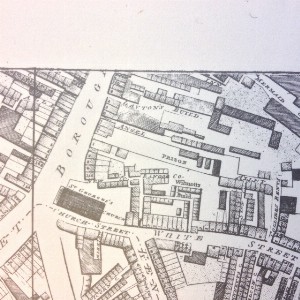

The last vestiges of the Marshalsea - the southern perimeter wall of the prison yard.

The Marshalsea Prison as shown on Horwood's map of 1813. On Christmas Eve 1811 the old prison, which had served for nigh on 500 years, was closed. The inmates were escorted the 130 yards south along Borough High Street to this, their new gaol, which served for just over 30 years, closing on 9 November 1842.

***Sugar Houses ( Part I ) Introduction

The following is the first of a series of short essays written by various scholars and historians describing London's Sugar Houses, many of which will appear on the LONDON 1840 model, but which have completely disappeared and are so little-known about today. They help illustrate what an extraordinary place London was at the beginning of the Victorian age.

".....my beat lying round by Whitechapel Church and the adjacent sugar-refineries - great buildings, tier upon tier, that have the appearance of being nearly related to the dock-warehouses at Liverpool....."

Charles Dickens, All the Year Round/The Uncommercial Traveller. 1869. Chapter 35.

There can surely be no vanished London building type more remarkable than the great sugar refineries of the Georgian and early to mid-Victorian eras. These astonishing buildings, better known in their day as sugar houses, and centred around Whitechapel and Wapping, ceased to exist, seemingly overnight, in the 1870s. Dickens, assuming the role of a policeman on his beat in East London, describes them perfectly - 'great buildings, tier upon tier'.

Up to ten storeys and 85 feet high, these were the tallest buildings in London excepting the churches, and would have completely dominated the areas around Leman Street, Wellclose Square, Pennington Street and Christian Street. Individually, they also covered a large area, often a whole block, with numerous auxiliary buildings such as stores, sheds, stock rooms and packing rooms, the counting house, a boiler house, scum house, the dwelling house of the proprietor or his manager, and often a men's room.

Whilst sugar refining started in London in the 16th century, it was not until the 18th century that it became a major industry, so much so that sugar was one of the most valuable imports into the country for the entire Georgian era and beyond. By the early 19th century there were around 120 sugar houses in the United Kingdom of which around 80 were concentrated in the East End, conveniently close to the newly built West India and London Docks. It was from here that the thick brown liquid, partially processed abroad and put into hogsheads (large casks), was despatched for the final refining process to separate pure sugar from the impurities.

These were incredibly dangerous and noxious buildings. The refining process relied on heat throughout, with smoke and fumes continually emitted, and such a high internal working temperature that they were prone to destruction by explosion and fire. This, combined with Government duties and newly established modern refineries down river, put paid to the industry in the East End. Many were demolished - some of them for the new London Board Schools which usually required a large site - whilst others were converted to new uses, especially warehouses, which were much in demand in the area bordering the City.

".....I had got past Whitechapel Church, and was - rather inappropriately for the Uncommercial Traveller - in the Commercial Road. Pleasantly wallowing in the abundant mud of that thoroughfare, and greatly enjoying the huge piles of buildings belonging to the sugar refiners....."

Charles Dickens, ibid. 1860.

The remains of the Sugar House belonging to Severn, King and Co., on the north side of Commercial Road, and the east side of Adler Street, Stepney, depicted here in 1820 following a catastrophic fire. It had been built in 1816 on land previously occupied as a pleasure ground, but was burnt down in 1819. The insurers refused to pay up, but the site was eventually rebuilt with better fire-proofing. In this scene a group of workers are clearing up the rubble. The refinery buildings tower above the two and three-storey houses in the adjoining streets.

***Late Georgian Cockspur Street and Charing Cross

Peter Guillery provides below a delightful vignette of Cockspur Street and its surroundings in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The construction of Trafalgar Square from the 1820s onwards, initially as part of Nash’s redevelopment of the West End, but then under the supervision of William Wilkins and Charles Barry, would radically transform this area over the next 25 years. This radical intervention will be very well illustrated in the 1840 model.

Late Georgian Cockspur Street and Charing Cross

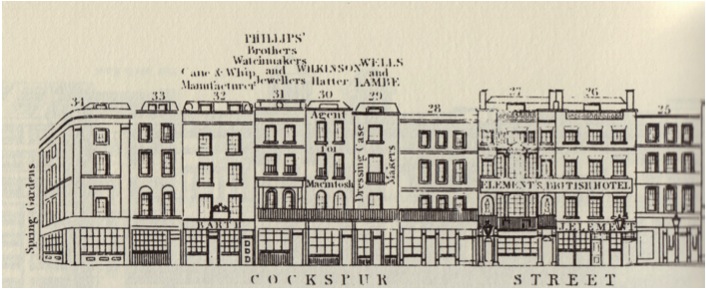

According to Samuel Johnson, the ‘full tide of human existence’ could be experienced at Charing Cross. This is not really evident in a superb Thomas Malton aquatint of 1797 looking west from Charing Cross along Cockspur Street. The place looks immaculate and orderly, and remarkably free of traffic. That is very probably artist’s licence, or it was a Sunday morning. To bottom left we can see the goldsmith Denis Jacob’s shop. Next door, but out of view was where Jacob’s brother-in-law Josiah Emery made and sold some of the period’s finest watches. There had been a robbery in 1781. Across the road is the Phoenix Fire Engine Station, erected to designs by Thomas Leverton in 1794. Next door to the west of the Fire Station was the Cannon Coffee House, a hint of the conviviality that was a strong part of the local scene – William Jones’s Mecklenburg Coffee House stood immediately adjoining to the north, hidden in Malton’s view. Also out of view on the south side of Cockspur Street was the British Coffee House at No. 27. This had its beginnings in 1710, but the premises were rebuilt in 1770 to designs by Robert Adam. The ‘British’ was long renowned as a place where Scots gathered. Tobias Smollett was a regular, Dr Johnson and Boswell dined there in 1772, as did Edward Gibbon with Garrick, Colman, Goldsmith, MacPherson and John Hume in 1774. In the early nineteenth century the establishment was extended to No. 26 and became John Element’s British Hotel. It was demolished in the 1880s. Elsewhere on Georgian Cockspur Street, Patience Lovell Wright, the American wax modeller who gained fame for her portrait busts, had set up shop by 1780. Her daughter Phoebe and son-in-law John Hoppner, the portraitist, lodged above. Malton’s prospect is terminated by the Italian Opera House on Haymarket, on the site of what is now Her Majesty’s Theatre. This eminent house had been rebuilt after John Vanbrugh’s theatre of 1705 was destroyed by arson in 1789. The new theatre opened in 1793, Michael Novosielski having been its architect. On the far right-hand side of Malton’s view is something quite different, a glimpse of a corner of the Royal Mews as rebuilt in the early 1730s to designs by William Kent. With the adjacent and no-doubt aptly named Dunghill Mews, this vast stabling complex must have brought a certain pungency to the otherwise urbane district.

Cockspur Street was a busy and commercial place, smart but not genteel, improving, but not improved. A witness from a generation later was Francis Place, the radical artisan, who in 1827 described what he could see from his window overlooking Charing Cross:

‘The fineness of the weather, the uncommon beauty of the horses in all the coaches, the sun shining on their well groomed skins, the hilarity they seemed to feel, the passengers on the outside gay and happy, the contrast of the colours of the clothes worn by the well dressed women outside the coaches, large bonnets made of straw, white silk or paper which at a distance has the appearance of white silk, all gaily trimmed with very broad ribbons woven in stripes of various bright colours running into one another like the colours in the spectrum, their white gowns and scarlet shawls, made the whole exceedingly lively and delightfully animating. The people in the street were variously grouped; workmen – market people with baskets of fruits and flowers on their heads, or on their donkeys, or in the small carts, numbers of others with vegetables, newsmen and boys running about to sell their papers to the coach passengers … a coup d’oeil which cannot be witnessed in another country in the whole world and perhaps at no other place in the world than at Charing Cross.’

A few months later Place enumerated being able to see from the same window and all at once 102 horses and 37 carriages, including ‘a wagon coming along loaded with Swedish turnips, drawn by six horses’.

Part 77 of “London Street Views”, by John Tallis, c.1838. showing the shops and houses of Cockspur Street.

View of Cockspur Street in 1809, looking towards the Haymarket, with figures and horse-drawn carriages; aquatint by Augustus Charles Pugin (1762-1832).

Cockspur Street, 1797; aquatint by Thomas Malton.

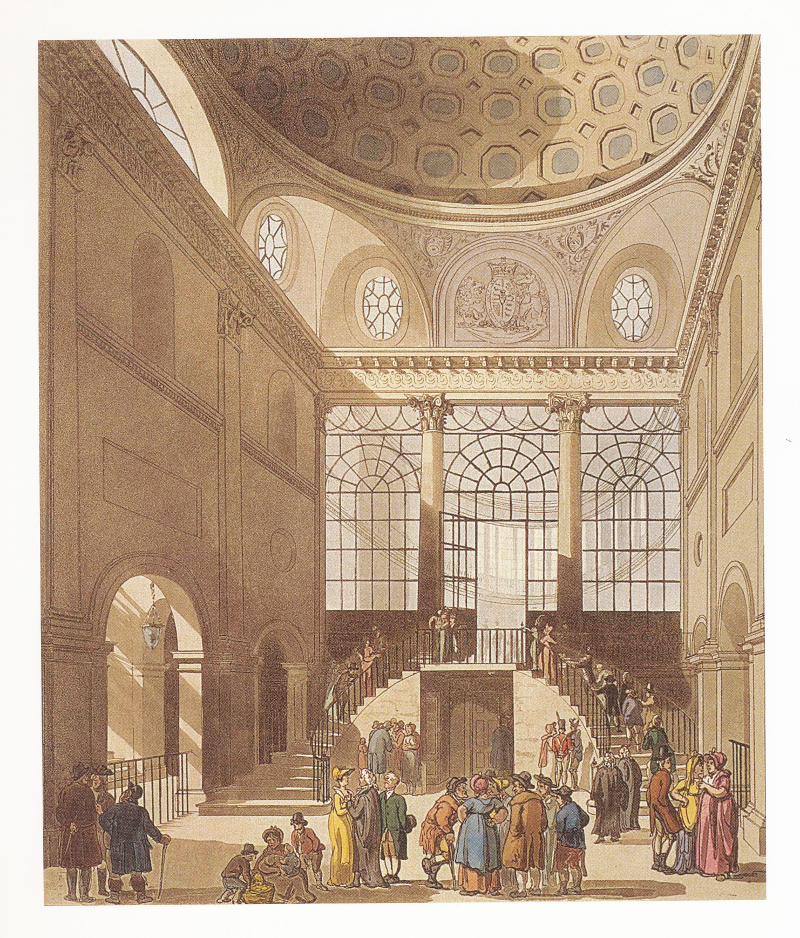

***The Glass Screen at the Middlesex Sessions House

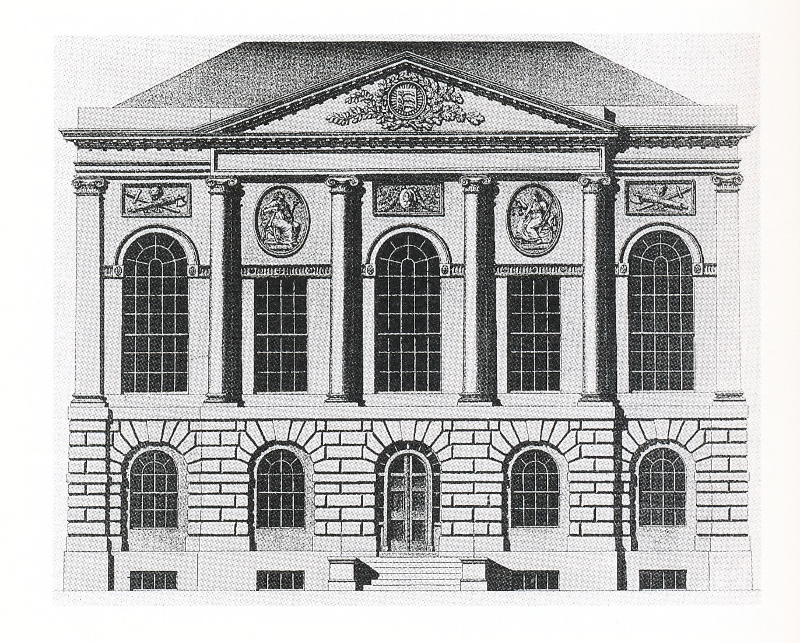

The construction of the Middlesex Sessions House began at the western end of Clerkenwell Green in 1779, to replace the cramped and dilapidated Hicks Hall that had previously dispensed justice at the bottom end of St John Street, immediately north of Smithfield livestock market. Construction work was interrupted by the Gordon Riots in the summer of 1780, but was completed in 1782. The new court house for the County of Middlesex was a high-status building, designed in opulent fashion, and was intended to impress, if not intimidate, the local population. Its location was also important. At the end of the 18th century 90% of all the crimes committed in the County of Middlesex occurred within a few hundred yards of the unruly cattle market and its surrounding slums and overcrowded rookeries. The nearby House of Detention in Clerkenwell Close held prisoners on remand; the House of Detention, slightly further north in Coldbath Fields, provided harsh punishment for those lucky enough not to be executed or deported. The new Sessions House, planned in a grand classical style by the Middlesex County architect and surveyor, Thomas Rogers, was meant to replicate the Roman system of ‘open court’. This, in theory, enabled the public to witness everything that happened, to hear what was said and to see that justice was done. The single double-height court room at first floor level was thus intended to be completely open to the domed public hall and entrance. Prisoners, held in the basement cells, were compelled to climb a simple narrow stone staircase to appear in the dock before the judge or magistrate. Those found guilty were sent back down to the cells, then to taken away to serve their sentence. Those found not guilty were released and could walk free into the public hall to join their jubilant or relieved friends and family. Within a few weeks of opening the judges and magistrates complained of the noise and unruly behaviour from the public hall, as well as the discomfort from the intolerable drafts. A full height glass and cast iron screen was therefore erected, designed by Rogers, which made life more comfortable for the judiciary whilst still allowing the public to see what was going on. Pugin and Rowlandson’s magnificent depiction of the public hall in 1808 shows the screen in all its glory. In the 1860s works by Roger’s successor as Middlesex County Surveyor, Frederick Pownall, replaced the lowest part of the glass screen with a solid plinth and two new doors. Other extensions and alterations were made to the building. A new staircase and landing was also created in the public hall to serve a second courtroom at the front of the building above the entrance. Thirty years late, when much of County of Middlesex was subsumed within the newly-created London County Council, the judiciary decided to build new court rooms at Westminster and Southwark. The Clerkenwell Sessions House was eventually closed and sold in 1921. From 1931 until 1973 it was occupied by Avery Scales, manufacturers of weighing machines, who carried out various invasive alterations, including inserting new mezzanine floors in the court room and many new partitions throughout the building. A new solid wall was erected between the domed hall and the court room. The glazed screen was apparently lost. From 1979 until 2011 the building was occupied as a Masonic Lodge. The masons retained most of what they found, applying their own distinctive decorative scheme, and a new layer of services. On their departure the future of the building was uncertain, but the new enlightened owners who acquired the Old Sessions House in 2014 were determined to do a scholarly restoration of the historic fabric, and find out more about what had actually survived the ravages of the 20th century. It was with great amazement therefore that exploratory openings in the back part of the solid wall between the domed hall and the upper part of the former court room revealed that substantial parts of the glazed screen had survived, sandwiched between two 20th century block-work walls. Experts were called in to supervise its complete uncovering, and subsequent repair, with the brave decision taken to reinstate the whole full-height screen as originally installed by Jones. A remarkable amount of the upper screen had survived intact, including quite possibly the largest amount of 18th century crown glass in the country. Perhaps the 20th century walls had served some purpose in protecting the glass against war-time bomb blast and vibration. The court room too has been restored to its original volume. Even the simple narrow staircase that carried the prisoners from cell to dock has been found and revealed, having been completed covered in and hidden from view for over 100 years. Now, once again, the principle of ‘open court’ and the method of dispensing justice in the reign of George III can be appreciated.

Front elevation of Middlesex Sessions House 1799, from George Richardson’s New Vitruvius Britannicus 1802.

The great hall and screen, as depicted by A.C.Pugin and Thomas Rowlandson in 1808, from Rudolph Ackerman’s The Microcosm of London.

The hall and screen as restored in November 2017.

All illustrations courtesy of Ted Grebelius.